The Divine Lover (Roswell, Ep. 1: Pilot)

Me Lord? can'st thou mispend

One word, misplace one look on me?

Call'st me thy Love, thy Friend?

Can this poor soul the object be

Of these love-glances, those life-kindling eyes?

What? I the Centre of thy arms embraces?

Of all thy labour I the prize?

Love never mocks,

Truth never lies.

O how I quake:

Hope fear, fear hope displaces:

I would, but cannot hope: such wondrous love amazes.

-- Phineas Fletcher, "The Divine Lover"

I saw me as he saw me, and the amazing thing was, in his eyes I was beautiful.

The 1999 version of Roswell, at least in the early going, is careful to avoid wholly endorsing the idea that Max Evans actually revives Liz Parker from a fatal gunshot wound. Though she opens the series by casually observing that "five days ago, I died," it's certainly not indicated in the healing scene itself, where she's just conscious enough to meet his gaze during the process. He dissolves the bullet, you see, before she crosses any final boundaries. “I’m not God,” he’ll remind her a few episodes later, after she petitions him to carry out a far weightier case of life from (near) death.

No indeed. Though otherworldly, Max, like fellow 1947 spaceship crash survivors Isabel and Michael (the aliens spent four decades in a state of suspended animation before emerging as elementary school-aged children in the early '90s), is also almost fully human, liable to hormonal agita and mortal danger. And to act as Liz's savior in the midst of a crowded, chaotic restaurant is to risk his own life; this is a catalyst, and those tasked with keeping order -- law enforcement, teachers, parents -- are naturally those most inclined to disrupt the aliens' own.

Midway through the episode, after Max has revealed his identity to Liz, Isabel speaks the threat aloud -- "some government agency, where they're gonna test us and prod us and exterminate us." It's no empty foreshadowing here when the focus zeroes in on Max's recognition.

The narrative may seem premised on the obvious tormented romance path; Liz provides a conventionally giddy voiceover after directly observing the magnitude of Max's inner affections for her. But this connection concerns higher stakes than the meeting of different worlds, and while Max's otherness facilitates the premise, it is not the story. Critics often shorthanded this show as Romeo and Juliet with aliens, but there's no Montague-Capulet war between species here, nor anything like the contemporaneous conflict of a slayer Buffy and vampire Angel or Spike -- or the subsequent supernatural angst of a Twilight series, where love is really hunger-motivation.

It shouldn't be missed that what metaphysically underlies these typical love battlefields is death -- suicidal lovers, monstrously immortal swains and the veil between realms. The test of devotion is mutual sacrifice, survivors be damned.

So one would be remiss to overlook how Liz ultimately concludes her journal entry: five days ago, she "came to life."

At the outset, this love is necessarily one-sided. The narrative, of course, requires Max's act of salvation to be unexpected -- before the shooting, Liz expresses disbelief at the idea he may be watching her as she waits tables; later, she is astonished by the depth of his feeling -- and it also demands development. One party ought to fall in love with the other, if the other is already there; better still if a genuine relationship can emerge from an intense but unspoken attraction.

But as the loves go, there is little in the way of overt eros driving the action, even despite an apparent sense of romantic chemistry. Max seeks nothing from Liz in return for saving her life and indeed recognizes she's safer without further engagement; it's only a sense of warranted curiosity on Liz's part that leads her to seek more from him in the way of answers. What's more, there's nothing offered to suggest Liz is of uniquely special worth in herself, or that Max is compelled by sexual ardor. "It was you," Max gives as the simple motivation behind his act. She is valuable because she is loved; she is loved for no particular given reason.

One could argue that an authentic demonstration of agape would demand Max regularly utilize his powers in a charitable fashion -- to the extent he simultaneously avoids endangering himself and those who benefit. This is perhaps not untrue. But as a work of storytelling, it's only through the singular connection that this love's gravity can be understood; no mystic focused her energies on explicating a broad, generalized relationship with God.

It is reasonably unlikely that any party responsible for Roswell's concept, from book series author Melinda Metz to show producer Jason Katims, intended their product to be read as divinely-tinged allegorical material. But the viewer is empowered to read what's presented, and for this adult's rewatch of an adolescent favorite, what's presented is a dynamic in some respects more Catherine of Siena than Shakespeare.

And as one final observation, let's just say that in an altered context, the show's most iconic moment has an air of familiarity.

Well, I'm not from around here.

Where are you from?

...Up north?

Much Missed Music

Eagle-Eye Cherry, "Save Tonight," a late '90s classic and originally Roswell's very first audio cut -- played over the introductory diner scene.

Funny Ha-Ha

MAX: I prefer the term 'not of this earth.'

LIZ: You have to promise me you are not going to flip out.

MARIA: Flip out? Hey, it's me.

*runs out screaming*

One word, misplace one look on me?

Call'st me thy Love, thy Friend?

Can this poor soul the object be

Of these love-glances, those life-kindling eyes?

What? I the Centre of thy arms embraces?

Of all thy labour I the prize?

Love never mocks,

Truth never lies.

O how I quake:

Hope fear, fear hope displaces:

I would, but cannot hope: such wondrous love amazes.

-- Phineas Fletcher, "The Divine Lover"

I saw me as he saw me, and the amazing thing was, in his eyes I was beautiful.

The 1999 version of Roswell, at least in the early going, is careful to avoid wholly endorsing the idea that Max Evans actually revives Liz Parker from a fatal gunshot wound. Though she opens the series by casually observing that "five days ago, I died," it's certainly not indicated in the healing scene itself, where she's just conscious enough to meet his gaze during the process. He dissolves the bullet, you see, before she crosses any final boundaries. “I’m not God,” he’ll remind her a few episodes later, after she petitions him to carry out a far weightier case of life from (near) death.

No indeed. Though otherworldly, Max, like fellow 1947 spaceship crash survivors Isabel and Michael (the aliens spent four decades in a state of suspended animation before emerging as elementary school-aged children in the early '90s), is also almost fully human, liable to hormonal agita and mortal danger. And to act as Liz's savior in the midst of a crowded, chaotic restaurant is to risk his own life; this is a catalyst, and those tasked with keeping order -- law enforcement, teachers, parents -- are naturally those most inclined to disrupt the aliens' own.

Midway through the episode, after Max has revealed his identity to Liz, Isabel speaks the threat aloud -- "some government agency, where they're gonna test us and prod us and exterminate us." It's no empty foreshadowing here when the focus zeroes in on Max's recognition.

The narrative may seem premised on the obvious tormented romance path; Liz provides a conventionally giddy voiceover after directly observing the magnitude of Max's inner affections for her. But this connection concerns higher stakes than the meeting of different worlds, and while Max's otherness facilitates the premise, it is not the story. Critics often shorthanded this show as Romeo and Juliet with aliens, but there's no Montague-Capulet war between species here, nor anything like the contemporaneous conflict of a slayer Buffy and vampire Angel or Spike -- or the subsequent supernatural angst of a Twilight series, where love is really hunger-motivation.

It shouldn't be missed that what metaphysically underlies these typical love battlefields is death -- suicidal lovers, monstrously immortal swains and the veil between realms. The test of devotion is mutual sacrifice, survivors be damned.

So one would be remiss to overlook how Liz ultimately concludes her journal entry: five days ago, she "came to life."

*

At the outset, this love is necessarily one-sided. The narrative, of course, requires Max's act of salvation to be unexpected -- before the shooting, Liz expresses disbelief at the idea he may be watching her as she waits tables; later, she is astonished by the depth of his feeling -- and it also demands development. One party ought to fall in love with the other, if the other is already there; better still if a genuine relationship can emerge from an intense but unspoken attraction.

But as the loves go, there is little in the way of overt eros driving the action, even despite an apparent sense of romantic chemistry. Max seeks nothing from Liz in return for saving her life and indeed recognizes she's safer without further engagement; it's only a sense of warranted curiosity on Liz's part that leads her to seek more from him in the way of answers. What's more, there's nothing offered to suggest Liz is of uniquely special worth in herself, or that Max is compelled by sexual ardor. "It was you," Max gives as the simple motivation behind his act. She is valuable because she is loved; she is loved for no particular given reason.

One could argue that an authentic demonstration of agape would demand Max regularly utilize his powers in a charitable fashion -- to the extent he simultaneously avoids endangering himself and those who benefit. This is perhaps not untrue. But as a work of storytelling, it's only through the singular connection that this love's gravity can be understood; no mystic focused her energies on explicating a broad, generalized relationship with God.

*

It is reasonably unlikely that any party responsible for Roswell's concept, from book series author Melinda Metz to show producer Jason Katims, intended their product to be read as divinely-tinged allegorical material. But the viewer is empowered to read what's presented, and for this adult's rewatch of an adolescent favorite, what's presented is a dynamic in some respects more Catherine of Siena than Shakespeare.

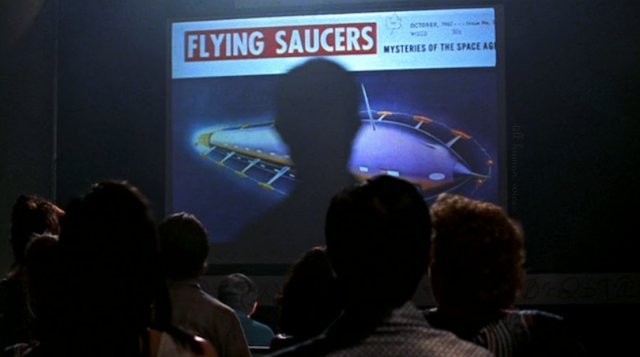

And as one final observation, let's just say that in an altered context, the show's most iconic moment has an air of familiarity.

Well, I'm not from around here.

Where are you from?

...Up north?

*

Much Missed Music

Eagle-Eye Cherry, "Save Tonight," a late '90s classic and originally Roswell's very first audio cut -- played over the introductory diner scene.

Funny Ha-Ha

MAX: I prefer the term 'not of this earth.'

LIZ: You have to promise me you are not going to flip out.

MARIA: Flip out? Hey, it's me.

*runs out screaming*

Comments

Post a Comment