Disturbing the Universe (Roswell, Ep. 2 and 3: The Morning After / Monsters)

Do I dare

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

*

And I have known the eyes already, known them all--

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

And how should I presume?

-- T.S. Eliot, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

Maybe Liz is earth -- too seen by her hometown, smothered by their awareness; in "Monsters," set on rigid plans and the fact-bound world. Max is, so to speak, space -- longing to be less invisible, less rootless; a high school junior who thinks that college is too far in the future to worry over, to deviate from his preferred strategy of quiet going-along-to-get-along.

Or, simply, she is proactive; he is passive, reactive at best. We can assume the former is the stronger path. Certainly few American editorials need to be written to mitigate anyone's guilt over direct action and efficient planning.

Max knows, in the abstract, what stasis has gotten him: the placid obliviousness of the one who senses they've missed a few rungs that others have scaled readily. When new guidance counselor Kathleen Topolsky invites him to identify himself in an illustration of children playing, he easily connects with the kid hiding behind a tree -- a "hard place to be," observes Topolsky, who says she'd been there herself during a few years of collegiate isolation. "It was really, really risky to change, to get out there in the world," she concludes. But Max grasps her point: the risk was worthwhile, and worthwhile risk for Max resembles awkward small talk with Liz, a girl with whom he's already shared something vastly more intimate. It's a curious divorce of roles here, the idea that Liz as romantic object must be separated from Liz as purely beloved. But it's also indicative of a running theme; if the Pilot established that this bond exists on an otherworldly plane, then the banality of high school romance is only made more explicit.

This is underscored, by the way, in "The Morning After," when an invitation from Max to Liz to meet in the notorious eraser room -- where many a classmate's virtue was compromised, in Maria's recounting -- is actually explicitly an invitation to spy on Topolsky, and implicitly occasion for an intensive meeting of the minds. It's here Liz seeks deeper knowledge of the aliens' lives prior to "[taking] human form," a time Max says he can't recall, though he takes the opportunity for a good gag about his hidden third eye. It's here too that Liz confesses the burden of being known to an entire community, every haircut and milestone commented upon by restaurant patrons and neighbors. "So you really have no idea where you're from?" she asks Max. "That must be kind of freeing in a way."

But this object of observation dreams of turning the microscope on a smaller target -- molecules, to be sure, maybe even as Harvard's head of molecular biology -- and the frankly naive view Liz takes of her field is telling in itself. "With science," she explains to Topolsky, "there are answers to everything. Facts. When you're conducting an experiment, you're in control of everything." Topolsky observes that Liz likes to be in control, likes to have plans, doesn't she? Liz, grimly, wryly affirms that one's got to have a plan. What about taking life as it comes? Obstinate and a little piqued: "No."

And here's the catch of it all: what they both seek, fundamentally, is control. If Liz fears the chaotic unpredictable, then Max's reluctance to engage is not just, as Topolsky suggests, a consequence of an unknown past or a desire for secrecy; it's also deeply protective. There's no disappointment in missing the object never reached for.

Fitting it is that Max's reactivity has introduced such a compelling detour on her steady course; that a surfeit of self-giving love for Liz has forced his readiness to accept the vulnerability of ceding oneself to the outside world

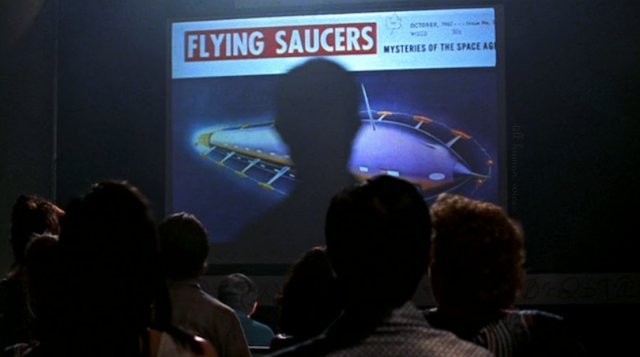

By Monsters' conclusion, Max, in pursuit of real truth, has taken on a convenient and fairly audacious job at the local UFO Museum. But Liz's next step -- for her, conversely, into the unknown -- will have to wait an episode.

Additional Allusions

"I'm just his sister, not his keeper," says Isabel when asked by Valenti in "The Morning After" about Max's whereabouts.

Funny Ha-Ha

As Liz delays sleep agonizing to her journal over the import of a seemingly innocuous "I'll see you at school" from Max -- "And what is he thinking right now? Is he also obsessed, tortured, going through one sleepless night to the next, wondering what's going to happen between us?" we smash-cut to...a snoring Max.

The introduction of the "Czechoslovakian as code for alien" running gag, appropriately lampshaded by Alex's later observation that Czechoslovakia as a country hadn't existed for 10 years.

*After Michael infiltrates the sheriff's office under the auspices of a candy fundraiser*

MAX: And they bought it?

MICHAEL: No, they all seemed to be on a diet.

Kyle flips out over Liz, Max, and a sight gag that went over my head in 1999.

Disturb the universe?

In a minute there is time

For decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.

*

And I have known the eyes already, known them all--

The eyes that fix you in a formulated phrase,

And when I am formulated, sprawling on a pin,

When I am pinned and wriggling on the wall,

Then how should I begin

To spit out all the butt-ends of my days and ways?

And how should I presume?

-- T.S. Eliot, "The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock"

Maybe Liz is earth -- too seen by her hometown, smothered by their awareness; in "Monsters," set on rigid plans and the fact-bound world. Max is, so to speak, space -- longing to be less invisible, less rootless; a high school junior who thinks that college is too far in the future to worry over, to deviate from his preferred strategy of quiet going-along-to-get-along.

Or, simply, she is proactive; he is passive, reactive at best. We can assume the former is the stronger path. Certainly few American editorials need to be written to mitigate anyone's guilt over direct action and efficient planning.

Max knows, in the abstract, what stasis has gotten him: the placid obliviousness of the one who senses they've missed a few rungs that others have scaled readily. When new guidance counselor Kathleen Topolsky invites him to identify himself in an illustration of children playing, he easily connects with the kid hiding behind a tree -- a "hard place to be," observes Topolsky, who says she'd been there herself during a few years of collegiate isolation. "It was really, really risky to change, to get out there in the world," she concludes. But Max grasps her point: the risk was worthwhile, and worthwhile risk for Max resembles awkward small talk with Liz, a girl with whom he's already shared something vastly more intimate. It's a curious divorce of roles here, the idea that Liz as romantic object must be separated from Liz as purely beloved. But it's also indicative of a running theme; if the Pilot established that this bond exists on an otherworldly plane, then the banality of high school romance is only made more explicit.

*

This is underscored, by the way, in "The Morning After," when an invitation from Max to Liz to meet in the notorious eraser room -- where many a classmate's virtue was compromised, in Maria's recounting -- is actually explicitly an invitation to spy on Topolsky, and implicitly occasion for an intensive meeting of the minds. It's here Liz seeks deeper knowledge of the aliens' lives prior to "[taking] human form," a time Max says he can't recall, though he takes the opportunity for a good gag about his hidden third eye. It's here too that Liz confesses the burden of being known to an entire community, every haircut and milestone commented upon by restaurant patrons and neighbors. "So you really have no idea where you're from?" she asks Max. "That must be kind of freeing in a way."

But this object of observation dreams of turning the microscope on a smaller target -- molecules, to be sure, maybe even as Harvard's head of molecular biology -- and the frankly naive view Liz takes of her field is telling in itself. "With science," she explains to Topolsky, "there are answers to everything. Facts. When you're conducting an experiment, you're in control of everything." Topolsky observes that Liz likes to be in control, likes to have plans, doesn't she? Liz, grimly, wryly affirms that one's got to have a plan. What about taking life as it comes? Obstinate and a little piqued: "No."

And here's the catch of it all: what they both seek, fundamentally, is control. If Liz fears the chaotic unpredictable, then Max's reluctance to engage is not just, as Topolsky suggests, a consequence of an unknown past or a desire for secrecy; it's also deeply protective. There's no disappointment in missing the object never reached for.

Fitting it is that Max's reactivity has introduced such a compelling detour on her steady course; that a surfeit of self-giving love for Liz has forced his readiness to accept the vulnerability of ceding oneself to the outside world

By Monsters' conclusion, Max, in pursuit of real truth, has taken on a convenient and fairly audacious job at the local UFO Museum. But Liz's next step -- for her, conversely, into the unknown -- will have to wait an episode.

Additional Allusions

"I'm just his sister, not his keeper," says Isabel when asked by Valenti in "The Morning After" about Max's whereabouts.

Funny Ha-Ha

As Liz delays sleep agonizing to her journal over the import of a seemingly innocuous "I'll see you at school" from Max -- "And what is he thinking right now? Is he also obsessed, tortured, going through one sleepless night to the next, wondering what's going to happen between us?" we smash-cut to...a snoring Max.

The introduction of the "Czechoslovakian as code for alien" running gag, appropriately lampshaded by Alex's later observation that Czechoslovakia as a country hadn't existed for 10 years.

*After Michael infiltrates the sheriff's office under the auspices of a candy fundraiser*

MAX: And they bought it?

MICHAEL: No, they all seemed to be on a diet.

Kyle flips out over Liz, Max, and a sight gag that went over my head in 1999.

Comments

Post a Comment